The Nile crocodile was a target of religious veneration for some ancient Egyptians and a source of terror to others.

Strabo witnessed these conflicting dispositions toward the crocodile amongst the Egyptians firsthand on a journey that he took up the Nile sometime in the late 1st century BC. He writes of how the inhabitants of Crocodilopolis worshipped a tamed crocodile named Suchus. The sacred reptile was kept apart by itself in a temple pond, and fed by the priests with offerings of bread, meat, wine, and other succulent delicacies (see footnote 1) [1]. Further up the Nile at the city of Dendera, however, we learn that the crocodile was utterly despised and regarded as ‘the most odious of all animals’. And the Denderans, according to Strabo, made every effort to track down and eradicate the creatures [2].

The Denderans were not alone in abhorring the crocodile. Writings that were already ancient by the time of Strabo emphasise the crocodile’s chaotic influence on the daily lives of the Egyptians. In The Teaching of Khety, for instance, we read of a fisherman blinded with fear upon coming face-to-face with a crocodile [3]. The menacing crocodile motif was also featured in cheesy New Kingdom love songs. In the song that I have in mind, a man swims across a crocodile infested river to reach his lover who is waiting on the other shore [4]. The pharaoh is sometimes reported to have hunted predatory animals feared by the common people. In one such writing, the pharaoh Amenemhat I boasts of having tamed a lion and taken a crocodile prisoner [5]. Lastly, it will be noted that the Nile crocodile did not confine itself to devouring indigenous flesh. For Aristotle records that one of Cleomenes of Naucratis’ servants was carried off by a crocodile when he served as governor of Egypt [6].

This, however, is a digression from which we must return to our main subject.

Herodotus records that the people dwelling around Elephantine, a city further up the Nile from Dendera, hunted down crocodiles not for the purpose of eradication, but as a source of food. He writes that crocodiles are hunted in many different ways, but confined himself to describing only the following technique [7]:

They bait a hook with a chine of pork and let it float out into midstream, and at the same time, standing on the bank, take a live pig and beat it. The crocodile, hearing the squeals, makes a rush toward it, encounters the bait, gulps it down, and is hauled out of the water. The first thing the huntsman does when he has got the beast on land is to plaster its eyes with mud; this done, it is dispatched easily enough – but without this precaution it will give a lot of trouble.

It seems to me that his concluding remark goes without saying. In any case, the hunting technique is imaginative and interesting, and one can understand why Herodotus deemed it worthy to record for his Greek audiences.

The historian Diodorus Siculus, a contemporary of Strabo, was evidently not entirely contented with the veracity and scope of Herodotus’ writings on crocodile hunting. Diodorus agrees with Herodotus that the catching of crocodiles using hooks baited with pork is an Egyptian technique, but he argues that it was employed only in very early times. The hunting methods employed at the time of Diodorus, we are told, involved the use of either heavy nets or iron spears from boats [8].

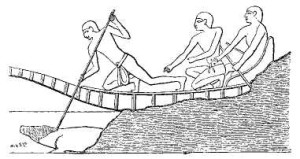

Let us return now in closing to Amenemhat I. The pharaoh is depicted above spearing a crocodile in a manner consistent with Diodorus Siculus. This illustration is taken from a history of ancient Egypt written by the 19th century English scholar George Rawlinson [9]. I have been unable to ascertain whether the illustration was copied from an ancient Egyptian source or produced from the unknown illustrator’s own imagination. But in either case there is a blatant inconsistency. Namely: how could Amenemhat have taken the crocodile prisoner to present in triumph before his astonished subjects, if he had speared the creature to death? Rawlinson notes the inconsistency, and speculates that Herodotus may well have been right, and that it was this technique Amenemhat employed to capture his reptilian prisoner.

Footnotes

[1] Crocodilopolis was the cultic centre for the worship of the crocodile-god Sobek. The city priests kept a sacred crocodile, named Suchus, in a temple pond that was believed to be the incarnation of Sobek by the Crocodilopolians. Suchus was adorned with gold and gem pendants, and fed by the priests with food provided by visitors. When Suchus died, it was mummified and replaced by another crocodile [10, 11].

References

[1] Strabo (1854). The Geography of Strabo, translated by Hans Claude Hamilton, esq. and William Falconer. Henry G. Bohn. Book XVII, Chapter I, Section XXXVIII to XXXIX. Read this passage at the Perseus Digital Library.

[2] Strabo (1854). The Geography of Strabo, translated by Hans Claude Hamilton, esq. and William Falconer. Henry G. Bohn. Book XVII, Chapter I, Section XL. Read this passage at the Perseus Digital Library.

[3] The Tale of Sinuhe and Other Ancient Egyptian Poems, 1940-1640 BC translated by Richard B. Parkinson (1999), Oxford World Classics, The Teaching of Khety. Read another version of this text at the West Semitic Research Project.

[4] Samivel (1955), The Glory of Egypt The Vanguard Press. Read this love song at the West Semitic Research Project.

[5] The Tale of Sinuhe and Other Ancient Egyptian Poems, 1940-1640 BC translated by Richard B. Parkinson (1999), Oxford World Classics, The Teaching of Amenemhat. Read another version of this text at the West Semitic Research Project.

[6] Economics by Aristotle; translated by George Cyril Armstrong (1935), Loeb Classical Library, Book II, Section 1352a. Read this passage at The Perseus Project.

[7] Herodotus (2003). The Histories, translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt and revised with introduction and notes by John Marincola. Penguin Classics. Book IV, Chapter II.

[8] Library of History by Diodorus Siculus; translated by Charles Henry Oldfather (1933), Loeb Classical Library, Book I, Chapter 35. Read this passage at Bill Thayer’s website.

[9] Ancient Egypt by George Rawlinson with the collaboration of Arthur Gilman (1886), tenth edition, London T. Fisher Unwin. Read about Amenemhat I hunting a crocodile at The Gutenberg Project.

[10] Margaret R. Bunson (2002). Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Revised Edition. Facts on File, Inc.. Read the entry on crocodiles at Google Books.

[11] Thomas Joseph Pettigrew (1834). A History of Egyptian Mummies: And an Account of the Worship and Embalming of the Sacred Animals by the Egyptians. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman. Read the passage on crocodiles at Google Books.

The method described by Herodotus is actually quite similar to how modern zoo keepers deal with crocodilians, and how I have myself, though rather than mud, a heavy, dark cloth is tossed over the eyes to allow the human to move unseen by the crocodile. Once the keeper can jump onto the animal’s back or otherwise catch it from behind, assuming they can avoid being shaken free, then can capture it relatively easily. Of course, if you mess up, you very well may wind up missing a few limbs, or a head, so kids, don’t try this at home.