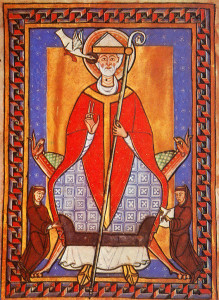

Zaleucus, 16th century portrait from Guillaume Rouillé’s iconography book entitled Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum.

Is there a modern-day Zaleucus? This question, which in the online age might not seem difficult, is actually one of the most difficult that a search engine has any business being asked. Before venturing to find an answer, however, certain preliminary questions must first be addressed. Who was this Zaleucus? Why is he remembered? What makes a modern individual worthy of being associated with his name? If such an individual is ever found, would he or she rebuke us? And above all: Does the search for a modern-day Zaleucus amount to anything more than an exercise of vain curiosity? In the following post I will attempt not only to answer these questions, but also to relate what I consider to be some noteworthy findings from my own failed search for a new Zaleucus to rebuke us in the online age.

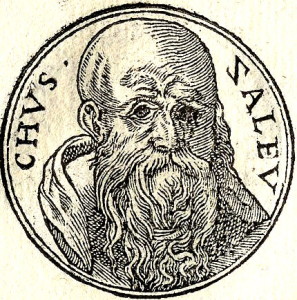

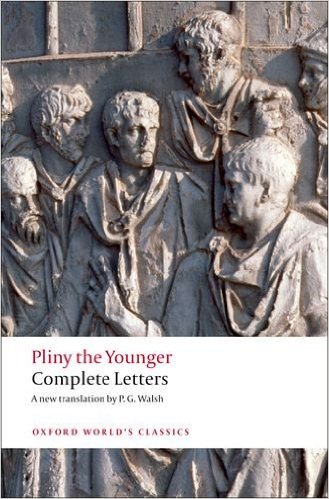

Illustration of three Atrophaneura zaleucus butterflies by British naturalist and butterfly collector William Chapman Hewitson from his 1865 work Illustrations of new species of exotic butterflies: selected chiefly from the collections of W. Wilson Saunders and William C. Hewitson, Volume I.

A quick Googling of Zaleucus will reveal that he was a celebrated lawgiver of Epizephyrian Locri, a Greek colony in southern Italy, and is said to have devised the first written Greek law code, the Locrian Code. One is also liable to uncover that Zaleucus has a Southeast Asian butterfly named after him, the Atrophaneura zaleucus [1]. It is generally held that Zaleucus flourished sometime in the 7th century BC and that his laws were very harsh. Little else is known about him with any degree of certainty beyond the few facts that I have mentioned. But according to a text attributed to Aristotle, he was a shepherd and slave who won his freedom upon being commissioned by the Locrians to draw up a law code as a remedy for civil unrest that prevailed amongst them [2]. The circumstances surrounding the Locrians choice of Zaleucus as their lawgiver is interesting. It further says in this Aristotelian work that when the Locrians consulted the Delphic oracle on how to bring about order in their city, they were instructed to make a set of laws. Zaleucus, in a bold move, announced to the Locrians that he could furnish them with very good laws. When asked how this could be, Zaleucus answered that the patron god of the city Athena had revealed them to him in a dream. Unwilling to challenge the lowly shepherd’s divinely granted authority, the Locrians consented and named him their lawgiver. The laws instituted by Zaleucus are said to have remained unchanged for more than two centuries, because anyone who proposed a new law that was not ratified was summarily strangled [3], and the Locrians subsequently enjoyed a high reputation as upholders of the rule of law [4].

Many laws attributed to Zaleucus have been preserved in the writings of ancient authors [5-7]. All of this is quoted extensively in Richard Bentley’s monumental work: A Dissertation upon the Epistles of Phalaris [8]. But sorting out which of these laws are traceable to Zaleucus from those that are later inventions is a matter of scholarly analysis. This is largely because a Pythagorean impostor is thought to have written a book of laws in Zaleucus’ name that was taken to be authentic by subsequent ancient authors. The book, Zaleucus’ Laws [7], most likely contained elements of the Locrian Code with significant Pythahgorean elaborations. This at any rate is the theory advocated by Bentley. Bentley further alleges that when the Locrians were confronted with this forgery, they quickly altered their laws to agree with it, although his source for this is unclear.

Ephorus of Cyme is one of the oldest and most trustworthy sources on Zaleucus. Through Strabo we learn that Ephorus taught that Zaleucus simplified the law of contracts and codified specific punishments for different offences, as opposed to previous lawgivers who left this to the discretion of a judge [9]. The penalty for committing adultery, if Valerius Maximus is to be believed, which he is not, was the the forfeiture of sight [10]. This brings us to the story for which Zaleucus acquired the lion’s share of his fame in ancient times. Valerius writes of Zaleucus:

His son was found guilty on the charge of adultery, and in accordance with the law that Zaleucus himself established, he should have had both his eyes gouged out. All the citizens, out of respect for the father, wanted to exempt the son from the rigours of the law, but Zaleucus resisted them for a long time. Finally, he was won over by the pleas of the people, so he gouged out one of his own eyes first, and then one of his son’s, thereby leaving each of them with the ability to see.

At first glance Zaleucus’ resolution of this difficult ethical dilemma might seem puzzling. After all, the rule of law was not followed and his son did not escape punishment. For Valerius, however, Zaleucus acted with wisdom by “dividing himself between the roles of a merciful father and a strict lawmaker.” The legend, then, under this view serves to illustrate the inherent conflict between the observance of the rule of law in society and the feeling of compassion toward other individuals that is part of human nature.

What then marks out a modern individual to carry the name Zaleucus into the 21st century? It is my contention that a modern-day Zaleucus must at minimum satisfy the following three conditions: he or she must 1) be responsible for the dispensation of justice, 2) be faced with a difficult choice between compassion and the rule of law, and 3) resolve the dilemma with a novel balance of compassion and justice.

Let us now proceed with an examination of the candidates.

Candidate 1: Police Chief Richard Knoebel

Former Village of Kewaskum Police Chief Richard Knoebel, circa 2007.

Former Village of Kewaskum Police Chief Richard Knoebel issued himself a $235 ticket for passing a school bus while he was distracted by a truck stopping on the other side of the street [11]. His decision is very disappointing from our present point of view. Had he donated the amount of the fine to, say, rent a bouncy castle for the school fair, then our search for a modern-day Zaluecus would have ended in triumph. The police chief, instead, chose to apply the law in a blind and reflexive manner. This is not in keeping with the example set by Zaleucus. Even the word “chose” must be used with caution here as it is unclear whether any other alternatives to the one he actually took scarcely entered his thoughts at all. His decision to give himself a four-point penalty on his drivers license only reinforces this conclusion.

Candidate 2: Christ

Christ with Instruments of the Passion by Jacopo d’Arcangelo del Sellaio, circa 1485.

The candidacy of Christ is controversial. According to the satisfaction theory of atonement, Christ suffered the Crucifixion as a substitute for human sin, satisfying God due to His infinite merit. Christ, then, plainly satisfies all three of the conditions laid out above. One might be tempted to dismiss His candidacy seeing that He is by no means modern, but the Bible assures us that the Son of man sits eternally at the right hand of God [12]. It will also be noted that while no butterfly is named after Christ, He is the creator of not only the Atrophaneura zaleucus, but also every other living thing that creepeth on the earth [13]. All of this is of course an elaborate fiction, far removed from the historical Jesus. And although unstated above, a basic precondition for consideration must be existence itself. This attribute cannot be said of the Son of man. It is on this ground that Christ is to be rejected.

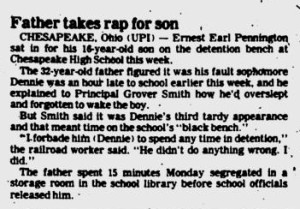

Candidate 3: Ernest Earl Pennington

Ernest Earl Pennington takes the rap for his son. The Bryan Times – November 19, 1980. Google News Archive

Railroad worker Ernest Earl Pennington of Cheasapeake, Ohio is an interesting, but ultimately unsatisfactory candidate. In 1980, Pennington sat in detention in place of his son Dennie on the school’s “black bench” in a storage room in the library. According to Pennington, he had overslept on the morning in question and neglected to wake Dennie, resulting in the boy arriving at school an hour late [14]. The father, who we may rightly admire, falls short of Zaleucus. This is because Pennington was not himself in a position to dispense justice. On top of that he differs from Zaleucus in so far as the lawgiver was in no way responsible for his son’s offence. If, hypothetically speaking, Pennington had been the school principal, and his son had arrived late of his own accord, and as principal he decided to split the detention time equally between them, only then would he merit being called the modern-day Zaleucus.

In the end, the question of whether there is a modern-day Zaleucus remains unanswered. Would a such an individual rebuke us? This question is imponderable in the absence of specific knowledge of his or her ethical outlook. But let the haters who regards the search for a new Zaleucus to be a vain curiosity consider these sobering words of Marcus Aurelius [15]:

How many who once rose to fame are now consigned to oblivion: and how many who sang their fame are long disappeared.

Indeed, if there is a new Zaleucus out there, it would be very sad should this individual live out life without ever attaining the modest amount of fame that he or she rightly deserves. It would be sadder still for humankind, if the new Zaleucus was “consigned to oblivion” without ever having received the opportunity to share his or her reflections on Youtube about this obscure historical parallel.

As a final note, I would be remiss not to thank my longtime friend Adam Clay for bringing Zaleucus to my general attention.

References

[1] Illustrations of new species of exotic butterflies: selected chiefly from the collections of W. Wilson Saunders and William C. Hewitson, Volume I (1865). These exquisite illustrations may be perused at The Internet Archive.

[2] Early Greek Law by Michael Gagarin, University of California Press, Reprint edition (1989), Page 58.

[3] Against Timocrates by Demosthenes, translated by A. T. Murray (1939), Section 141. Read this speech at The Perseus Project.

[4] Timaeus by Plato, translated by W.R.M. Lamb (1925), Section 20a. Read this passage at The Perseus Project.

[5] Diodorus Siculus I: The Historical Library in Forty Books (Volume 1), translated by Giles Laurén (2014), Book 12, Chapter 20, Section 1. Read this passage from the Loeb Classical Library, 1946 edition at Bill Thayer’s online collection of classical texts.

[6] Histories by Polybius, translated by Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (1886). Read Polybius’ passage about the laws of Zaleucus at The Perseus Project.

[7] The Anthology of Joannes Stobaeus. (I’m still working on this source.)

[8] The Works of Richard Bentley, Volume 1, Dissertations upon the Epistles of Phalaris, collected and edited by Alexander Dyce (1836). The original book has been digitised and made available for viewing and download at The Internet Archive

[9] Strabo’s Geography, translated by H.C. Hamilton, Esq., W. Falconer. Book 6, Chapter 1, Section 8. Read this passage at The Perseus Project

[10] Valerius Maximus: Memorable Deeds and Sayings: One Thousand Tales from Ancient Rome, translated by Henry John Walker (2004).

[11] Police Chief Writes Himself Ticket, WISN 12 News – January 30, 2007.

[12] Luke 22:69

[13] Genesis 1:25

[14] Father Takes Rap for Son, The Bryan Times – November 19, 1980. Google News Archive

[15] Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, translated by Martin Hammond, Penguin Classics, (2006).

![The Table of the Sun God is an article on the Frédéric Cailliaud expedition to the ancient city of Meroë that appeared a 1968 issue of the British educational magazine for children Look and Learn [11]. Image licensed for educational use (LL0362-015-00).](http://www.anecdotesfromantiquity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/The_Table_of_the_Sun_God-782x1024.jpg)