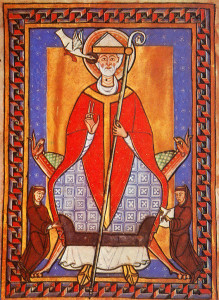

Saint Gregory the Great (c. 540 – 604) was pope from 590 until his death. He is depicted here on the throne in full papal regalia in an illumination from a 12th century French manuscript on his works. The manuscript is presently housed at Bibliothèque Municipale de Douai.

Saint Gregory the Great is for me the most interesting character in all of early Christendom.

Gregory was born in Rome of a rich aristocratic family around the year 540 at a time of considerable upheaval in Italy. His boyhood was passed amidst a disastrous conflict between the Ostrogoths and the Eastern Roman Empire that saw the Eternal City sacked in 546 and besieged on a number of separate occasions. In spite of these disturbances, the young Gregory received a reasonably good education in the classical liberal arts. He mastered Classical Latin and is said to have excelled in grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric, but seems never to have learned even rudimentary Greek (see footnote 1).

In early adult life, he took an active part in civic affairs and became Prefect of Rome when he was little more than thirty years old. It must be emphasised that Gregory was stinking rich. He resided in a private villa, centrally located on the Caelian Hill with a view of the dilapidated palaces of the Roman emperors. His family, moreover, held large estates in Sicily and around Rome. But just when it seemed by all outward appearances that Gregory was poised to live out a life of worldly splendour, he resigned his office, donated his wealth to the establishment of monasteries, himself living as a monk in his villa, which he converted into a monastery dedicated to the apostle Andrew.

Gregory was reluctantly drawn out of his seclusion in 578 when the pope dispatched him to the Court of Byzantium on a diplomatic mission to secure military aid against the invading Lombards. Although Gregory’s efforts in this pressing matter were ultimately unsuccessful, his six year stay was not in vain. He triumphed over the Patriarch of Constantinople in a prolonged theological dispute concerning the palpability of resurrected bodies. The patriarch’s contention that resurrected bodies would be “more light than air” was deemed heretical and his books were burned. The dispute is said to have taken such a toll on the patriarch that he fell ill and died. Gregory too fell seriously ill from the strain of the struggle, but recovered. He was recalled to Rome in 585 and returned to his monastery-villa where he was soon made abbot. At the same time, he served as chief advisor and assistant to Pope Pelagius II until 590 when the pontiff died of a plague that was ravaging the city.

Gregory was elected against his will to succeed Pelagius as pope. He came to power at a time when anarchy prevailed across much of Europe. To make matters worse, he was in constant ill-health probably owing to years of monastic asceticism. His pontificate, which lasted fourteen years, was nevertheless more instrumental in shaping the future of the Church than that of any of his successors until arguably Gregory VII’s almost five centuries later. Gregory worked tirelessly to fill the power vacuum left by the Eastern Roman Empire. He did much to centralise Church authority in Rome, primarily by means of disseminating a bishop code of conduct and taking an authoritative tone in written correspondences that he maintained with bishops around the Roman world. He completely reformed the administration of Church territorial possessions and promoted international social cohesion by launching efforts to convert the Lombards and the English. In short: Gregory almost single-handedly laid the foundations for the institution of the medieval papacy. On top of all that he wrote a number of influential letters, books, and homilies; many of which have survived to the present day.

Dialogues [1] is the one work by Gregory with which I myself am best acquainted. It is a four volume collection of fanciful tales concerning miracles, omens, and other thaumaturgical wonders written in 593 at the behest of his monks. And one cannot read it without wondering how a consummate statesman and administrator like Gregory could have taken seriously the kinds of cockamamie superstitions that pervade its pages. Reconciling these discordant aspects of Gregory’s character disturbed me for a time, but then I remembered reading somewhere or another how Ronald Reagan believed in astrology, lucky charms, and Reaganomics. All this just goes to show that one can be credulous in intellectual matters and still be esteemed as a master of statecraft.

Be that as it may, in what follows, I would like to share a story from Dialogues that helps to illustrate the strange and gloomy mental world Gregory and his contemporaries must have inhabited. Indeed, conspicuous among the extraordinary tales of medieval Christian lore recorded by Gregory is the rather sad account of a blasphemous young boy who was carried off to the devil by a hoard of spectral blackamoors.

“Seeing mankind is subject to many and innumerable vices,” says Peter the Deacon, friend and disciple of Gregory, “I think that the greatest part of heaven is replenished with little children and infants.”

Gregory concedes that all baptised infants who die in their infancy are to be counted among the elect, but goes on to provide a grim demonstration of the fate of those children who are hindered from heaven by a parents’ lenient upbringing.

“For a certain man in this city,” recounts Gregory, “some three years since had a child, as I think five years old, which upon too much carnal affection he brought up very carelessly: in such sort that the little one […] so soon as anything went contrary to his mind, straightways used to blaspheme the name of God.”

We learn moreover that the boy was soon thereafter stricken with a mortal illness. Nearing the point of death, and in his father’s arms, the child beheld with “trembling eyes” certain wicked spirits coming toward him. He then rose up from his father’s bosom and cried out to him, “Keep them away, father, keep them away.”

“My son, what vexes you so?” said the father, no doubt somewhat taken aback that his son did not there behold the holy Apostles, Saint Peter and Saint Paul.

“O father, there be blackamoors come to carry me away.”

And with his final words, the boy once again blasphemed the name of God, because as Gregory contends, the Lord wished to make it known to the world for what sin the lad was delivered up to the hell fires by such terrible executioners.

Thus concludes our admittedly depressing glimpse into the mind of Saint Gregory the Great.

Footnotes

[1] Gregory’s ignorance of Greek has been a persistent source of surprise to modern commenters, since Gregory was dispatched to Constantinople on diplomatic service for the better part of six years. As someone who has lived in Japan for about the same amount of time, however, I can empathise with Gregory on this point, seeing as my Japanese still sucks.

References

[1] Gregory the Great (1911). The Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great, translated by P. W. and reedited with an introduction and notes by Edmund Garratt Gardener with illustrations from the old masters annotated by Sir George Francis Hill. Philip Lee Warner. Book IV, Chapter XVIII (pages 199-200). Read this passage at the The Tertullian Project. The original book has been digitised and made available for viewing and download at The Internet Archive

The moral of this story seems to come very close to contradicting Ezekiel 18:20. What are your thoughts?

I guess Gregory preferred Deuteronomy 5:9… In all seriousness, though, I suppose he would have had to maintain that the boy was morally responsible for his blaspheming, strangely as that might strike us today, seeing as he was only five years old. Any thoughts?

I came here after listening to a priest relate this story in a homily. Apparently, this gloomy type of thinking is not limited to Gregory’s time. https://youtu.be/p9hVNHM2YvE

To be honest, part of me is open to this as a possibility

Very sad for that poor boy. I think we should all do our best to avoid blackamoors in this life, and Hellfire in the next!