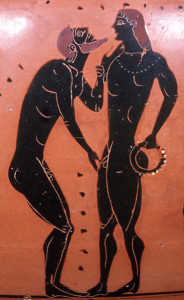

Pederastic courtship scene depicting a grown man fondling the genitals of a young man from an Attic black-figure neck-amphora, ca. 540 BC; photograph by Haiduc, distributed under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

Apollodorus records that the first gay guy was a musical bard named Thamyris and that he loved the youth Hyakinthos [1]. Although Hyakinthos was loved by Thamyris alone among mortal men, the youth was also greatly admired by the god Apollo and by the god of the West Wind, Zephryos. Hyakinthos, for his part, was ultimately partial to the affections of Apollo. The three rivals vied over Hyakinthos in a jealous struggle that ended with both mortal men suffering tragic fates, after having partaken in the sexual exploits of the gods.

The tale begins with Thamyris, a Thracian by birth, who is credited as being the mortal discoverer of homosexual love. Whether he hit upon the notion by means of idle contemplation or he merely followed in the example set by the gods is a matter of speculation. It seems probable, however, that Thamyris would have discovered homosexual love in spite of the gods, as he is stereotypical of the sort of character one would expect a man confronted with latent homosexual compulsions to be like. He was by all accounts a temperamental man with an inherent talent in music. He excelled both in the lyre and in song. Pliny the Elder wrote of him that he invented the Dorian mode and was the first man to play upon the lyre without vocal accompaniment (see footnote 1) [2]. In ancient art he is habitually depicted wearing fine robes, and in some instances dons a laurel wreath. On top of all that he was also a vain man, who was fond of boasting that he surpassed even the Muses in musical ability.

Roman mosaic of Zephryos, god of the West Wind, dating from the 2nd or 3rd century AD; image distributed in agreement with the Theoi Project copyright.

In whatever way it was that Thamyris came to desire the companionship of another man, he at some point fell passionately in love with the youth Hyakinthos. Hyakinthos was of aristocratic birth and a man-dazzler of the highest order. Indeed, one cannot help but to imagine him to have been a slim but muscular youth with a dainty step and a delicate utterance — an aesthetically delightful embodiment of masculinity. As it happened, he too was gay. In recognizing this, however, the lad was much indebted to the influence of Thamyris. For about the time his beard had only just begun to grow, Thamyris set about plying him with wine and beautiful music, revealing in dactylic hexameter the unsettling forces at work within him. Once he surmised that Hyakinthos was on the verge of succumbing to temptation, he cast off his garments and threw himself at the bewildered young man. Hyakinthos fended off his lusty advances for a time, but in the end Thamyris prevailed, and they proceeded to consummate their union with a bout of vigourous lovemaking.

While they began their relationship with enthusiasm, it was not long before Hyakinthos grew restless, owing largely to the fact that he had caught the attention of Apollo. Thamyris urged his beloved to refrain from flirting with the god of music and healing, who also happened to be the director of the choir of the Muses. But his efforts were to no avail. Apollo soon succeeded in stealing the lad’s heart to the great anguish of Thamyris. The pair subsequently carried on in a protracted love-affair, presumably meeting whenever Thamyris was off performing to the merriment of his audiences or was otherwise occupied composing his epic poem on the war of the Titans against the gods (see footnote 2).

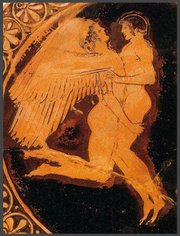

Depiction of Zephyros and Hyakinthos copulating in midair from a drinking cup signed by the artist Douris, ca. 490 – 480 BC. The drinking cup is currently housed at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

On one such occasion Zephyros chanced upon the happy lovers frolicking in a meadow. This is not surprising because we know from classical sources that Zephyros lived in a nearby cave. At any rate, the harbinger of Spring thought Hyakinthos so fine that he resolved to make the boy his own. Hyakinthos was willing to have the odd romantic encounter with Zephyros, which he on occasion did, but drew the line at commitment of any kind. Although little else about their relationship has survived in the writings of classical commentators, there is a compelling piece of evidence from the archeological record to suggest that it was believed to be marked by acts of extraordinary depravity. The artefact to which I refer is a drinking cup, painted with a scene that shows Zephyros whisking away Hyakinthos like a thing possessed, for what one can only fathom was to copulate with him in midair, while the entire Thracian populace gawked in stunned amazement.

The real trouble began, however, when Apollo resolved to dispose of Thamyris by means of a cunning appeal to his vanity. In this effort he was wholly successful. Apollo held a lavish banquet for Thamyris with singing and dancing courtesy of the Muses, ostensibly in recognition of the bard’s achievements in music. But his true motive became apparent once he informed the Muses of Thamyris’ boast of being a superior musician. To settle the matter they agreed to take part in a musical contest in which the winner was obliged choose a punishment for the loser (see footnote 3). The Muses won by the popular acclaim of the attendees; whereupon Thamyris was deprived of his musical talents, and either blinded or maimed and beaten with rods. Although it must be said that Pausaunias maintains that Thamyris lost his eyesight from disease, just as Homer had himself [4]. What is certain is that Thamyris ultimately gave up on Hyakinthos in despair.

Once this grisly episode was finished, Hyakinthos consented to become Apollo’s boy-favourite, leaving Zephyros as the odd man out. Then one day, after searching high and low, Zephyros found the youth and the god playing catch with a discus in a field. Zephyros asked if he could play too, but Apollo refused and sent him scurrying away with a volley of arrows. The interloper took refuge in a nearby tree, from where he watched in secret as the lovers resumed their game. The sight of them, however, was more than Zephyros could bare. As Hyakinthos pranced with arms outstretched to catch a toss from Apollo, Zephyros, overcome by jealousy, blew on the discus, sending it careening toward the lad’s head. It struck and he was inflicted with a critical wound. A vengeful Apollo fired once again on Zephyros as he fled, but the arrow missed its mark. The god then hurried over to his beloved and treated the wound with ambrosia and nectar; however, these heavenly foods proved to be an ineffective remedy, and Hyakinthos died. Afterwards, Apollo made a flower, the hyacinth, spring from a pool of his departed lover’s blood as a token of his affection.

Footnotes

[1] One wonders whether Oscar Wilde had the story of Thamyris and Hyakinthos in mind when he wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray.

[2] This work attributed to Thamyris is mentioned in the essay De Musica that was once believed to be authored by Plutarch [3]. Sadly it has not survived to the present day.

[3] The ancient Greeks were presumably more accustomed to such a contest than are modern people.

References

[1] The Library by Apollodorus; translated by Sir James George Frazer (1921), G. P. Putnam’s sons; accessed from Perseus Digital Library on May 17, 2015.

[2] Natural History by Pliny the Elder; translated by Horace Rackham (1938), Harvard University Press, Book VII, Chapter 204; accessed from Loeb Classical Library on May 17, 2015.

[3] Plutarch’s Lives by Pseudo-Plutarch; translated by William Watson Goodwin (1874), Little, Brown & Co., Volume 1, pages 102-135; accessed from Google Books on May 17, 2015.

[4] Description of Greece by Pausanias; translated by W. H. S. Jones (1918), G. P. Putnam’s sons, Book IV, Chapter 33; accessed from Perseus Digital Library on May 17, 2015.

Wikipedia suggests that it might be an iris or another flower, which is odd considering the name. Adonis, though, is a genus of flowers that actually don’t represent the flower of myth. In myth, it was the blood red anemone, not the blood red adonis flower, that came from the blood of Adonis. (They are in the same plant family but are not the same genus. The flowers are similar but the anemone is much larger.) So, the correct flower there got mixed up with time.